Women workers face new realities

In a three-part series starting today, Mint examines the issue of informal labour from the perspective of such women, whose traditional roles are changing in the face of India’s transformation

Cordelia Jenkins & Malia Politzer

New Delhi: The economic future of urban India has its foundation in a vast and amorphous force of informal labour.

In April, a McKinsey and Co. study estimated that by 2030, nearly 590 million Indians will live in the cities— roughly twice the population of the US. This urban boom is a combination of factors: a massive pull from development, construction projects and increased demand for domestic staff from a growing middle class.

Nuclear families with two working partners are becoming more common in the cities and, without the support of an extended family, domestic servants have become a necessity.

These trends have catalysed the mass movement of migrant workers to the cities in search of better job opportunities. Such workers, particularly the women, are becoming the driving force behind urbanization and the crutch that supports India’s economic expansion.

A recent study of domestic workers in the slums of Delhi by the Indian Social Studies Trust found that nearly 80% of them were migrants, 41% of whom said they came to Delhi for jobs as domestic workers.

Yet they remain a largely invisible force, working in the informal economy as maids, cooks and nannies, unprotected by labour laws and frequently falling prey to social exclusion and financial, physical and sexual exploitation. Perhaps the most vulnerable are the single women who flock to the cities with spurious “placement agencies” to work as live-in maids and those who fall prey to traffickers. But there are positive outcomes too.

In Delhi, married women moving their families into urban slums have become the primary bread earners. In Bihar, village women who have all but lost their men to seasonal migration must figure out how to function as the de facto household heads.

In a three-part series starting today, Mint examines the issue of informal labour from the perspective of such women, whose traditional roles are changing in the face of India’s transformation.

In the shadow of abuse, exploitation

With no regulatory oversight, dishonest agencies are placing domestic help in a legal and economic vacuum

New Delhi: Bardani Logun sits on a plastic chair in the communal room of a hostel in Rohini, north Delhi, where she lives with her toddler, and speaks candidly about being beaten, abused and starved.

She is one of countless young women from the tribal belt of India who have migrated to Delhi to find work as live-in maids, hoping to send their earnings back home to support impoverished families in Jharkhand, Orissa, Chhattisgarh or West Bengal. Like many others, Logun found work through a placement agency, which promised to find her a full-time job and a secure salary living with a Delhi family.

The reality was grim. Her employers kept her trapped in the house, bullied and starved her. “I worked for them for only a month,” she says, “and then I couldn’t stay any more.” The placement agency withheld her wages and she couldn’t afford the train fare home. Logun and her daughter, Theresa, were stranded homeless in Delhi until they found the hostel run by Nirmala Niketan, a non-governmental organization (NGO).

As her mother speaks, Theresa runs about with the other boys and girls who stay in the hostel, shrieking with laughter in the glare of a muted TV set in the corner. Other women listen in. Each has her own tale to tell and the accounts are depressingly uniform: a litany of sexual or physical abuse, stolen wages and isolation; they illustrate a wide-spread, but largely unacknowledged, problem.

While there is surging demand for household help in metros such as Delhi, the absence of a regulatory framework has led to the emergence of a shadow industry of placement agencies, spiking from a handful at the start of the decade to more than 1,000 today in the Capital alone.

In the absence of oversight or registration requirements, these agencies are given free rein to recruit and place women in private homes without being held accountable for their working conditions. Worse, in some instances, agents have been guilty of trafficking girls, forcing them into bonded labour or prostitution and stealing their wages.

The problem

Domestic work is not recognized under India’s labour laws, nor is it included under the minimum wage law in most states. As a result, agencies are not required to retain lists of women placed, or records of employers.

“Workers are not being told the conditions under which they are being placed. They might not know how much their salary is, how much commission the placement agencies will take, or when they will get paid,” says Neetha Pillai, a senior fellow at the Centre for Women’s Development Studies, a think tank. As a result many women move from one exploitative situation to another.

According to Pillai, agencies create a network of locals in the villages who are paid about Rs. 1,000 per head for every girl they send to the cities. Grace, who uses only one name, was only eight years old when she was first brought to Delhi, by a neighbour who helped find her a job through an agent.

Now 17, she wears a green kurta and a bold, somewhat combative, expression as she describes the abuse she suffered. “The mother would slap me and shout at me,” she says. After four years of abuse, Grace went to the agency for help. “I cried in front of them and said that I didn’t want to stay here any more; I said I wanted to go home.” The agent refused to pay Grace her wages and instead placed her with another family.

Her next employer was equally harsh. “She said that I didn’t know anything, that I was from the jungle and I was ignorant. She said it was God who was providing me with shelter and a home and that I should feel lucky to be there. It built up her pride to make me feel lower than her,” Grace says.

She was kept inside, even prevented from going to church on Christmas Day, until a neighbour’s maid intervened and told Grace about Nirmala Niketan, a women’s cooperative that acts as a placement agency, children’s hostel and safe house for domestic workers in need.

Subhash Bhatnagar, who has been running Nirmala Niketan for six years, has regular dealings with employers and notes that dishonest agents exploit them too, holding them to ransom over commission fees and availability of staff.

For some girls, the outcome is even worse—the brothels in places such as GB Road in Delhi are full of migrant women. According to Ravi Kant, of the anti-trafficking NGO Shakti Vahini, most of the girls on GB Road are either from Nepal or the tribal belt. Most, he says, were recruited by local agents who promise good jobs as domestic workers.

Unsafe migration

A 20-year-old from a poor village in Andhra Pradesh is one such victim. She was brought to Delhi by an acquaintance from her village who promised to help place her with a good family as a maid. Instead, she was sold to a brothel along GB Road. There she was raped, beaten and forced to have sex with nearly 40 men daily. She was one of the lucky ones—she was rescued by the Delhi police and Shakti Vahini after her family filed a missing persons report. Most women do not escape.

“There’s a breaking-in period,” says Asha Jayamaran, who works at anti-trafficking NGO Apne Aap. “They are raped repeatedly, tortured such as burnt with cigarettes, blackmailed, threatened that their families will be hurt. By the time the breaking-in period is complete, they suffer a sense of shame and guilt and do not want to return to their villages.”

It’s hard to say how many women are trafficked into prostitution by dishonest placement agencies, but villages are rife with stories of missing girls. And once a girl disappears, it’s virtually impossible to track her down.

“There is a big link between unsafe migration and trafficking,” says Kant. “A lot of the unskilled labour is coming to Delhi in search of the migrant dream. But they don’t necessarily know where to look, so they rely on placement agencies, who say they’ll place them in homes. Instead they’re sold to brothels, or placed in prostitution rackets and sent to various villages in Haryana, Delhi and Punjab. Migration gone wrong becomes trafficking.”

Most activists and experts advocate formalizing the connection between agents and employers by mandated registration as a way out of this destructive cycle. The fact that Delhi’s live-in maids exist in a legal and economic vacuum (often without bank accounts or identification papers) makes them virtually untrackable, unprotected by law and liable to disappear without a trace.

Easier said than done

“Yes, placement agencies have to register—but they don’t have to say what they do,” says Reiko Tsushima, a specialist on gender equality and women workers’ issues, at the International Labour Organization (ILO). “Agencies can be registered as societies, trade unions, trusts, NGOs—but there aren’t any audits or mechanisms for labour checks.”

However, this is easier said than done. There have been attempts to regulate the industry since independence (nationally, there are around 11 versions of Bills to regulate and improve conditions of domestic workers), but none has succeeded in becoming law. In 2008, the National Commission for Women (NCW) attempted to address some of these issues in a Domestic Workers Bill, which would require compulsory registration of agencies, employers and workers and regulate working conditions. However the Bill never made it past the draft stage.

With legal recourse not readily available, the only hope is a clutch of not-for-profit organizations. Bhatnagar, for instance, is working through Nirmala Niketan to try to establish a system by which girls can return home, but he acknowledges that it won’t be easy. There’s also the problem of sexual abuse and its stigma in the villages. In fact, according to Pillai, rape is so common that some agencies inform girls at the outset that they will pay for an abortion should a pregnancy occur. But because many of the girls are Christians, they refuse to have abortions, and are consequently excluded if they try to go back. Returning home can be a more daunting prospect than leaving, says Bhatnagar. “Their families don’t want them to come back or get married. In the long term, these girls are stuck here.”

It isn’t surprising then, that despite everything that’s happened to her in Delhi, Bardani Logun won’t go back to her village. Her in-laws don’t want her any more, she says, and she can’t survive alone. Similarly, Grace has nothing to return to: “My parents didn’t take an interest in my life, they only wanted the money.” For most girls, the journey back to the village will remain an unrealized goal.

Bringing home the bread

Multiple part-time jobs offer the chance of higher wages to migrant women, but they come with a lack of security

New Delhi: The Karkardooma slum is hidden in plain sight. Tucked behind a billboard, makeshift houses of cinder blocks and corrugated steel crowd narrow lanes, just a short walk from the manicured gardens and three-storey bungalows of Anand Vihar, in the eastern part of Delhi. Small children play marbles under the watchful eye of the neighbours. Shobha Kumari, a resident of the slum, wakes up every day at 5.30 in the morning, cooks for her four children and husband and then leaves for work—she is a part-time help.

Her actual home is Madhya Pradesh. The family moved to Delhi many years ago, like other families in similar circumstances, to look for a better existence. Unlike in the village, there are jobs aplenty for women like Kumari in the city, albeit poorly paid and with no security. By working at several homes in the neighbourhood and charging Rs. 200 per month for each of the services rendered—sweeping and washing dishes, for instance—these women have managed to survive outside of the network of placement agencies. In many instances, they are slowly replacing their husbands as primary bread earners.

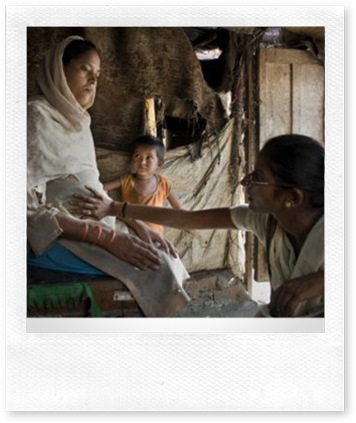

Helping hand: Jyoti, a grass-roots organizer of the Self Employed Women’s Association, tells a part-time domestic worker about her rights.Photographs by Ankit Agrawal/Mint

As a result, for the first time, married migrant women from rural India have become independent wage earners, a phenomenon that is triggering its own social dynamics and which offers yet another face of urban migration.

The new bread earners

Although working part-time affords Kumari a certain degree of independence, her schedule is still largely dictated by her employers. There is no question of missing a day of work if she becomes sick. “If you miss more than three days of work, they replace you,” she says.

Part-time workers in Delhi are increasingly in demand, according to Bina Agarwal, director and professor of economics at the Institute of Economic Growth. “Earlier you only had live-in domestic help, but now families are more nuclear, space is constrained, it’s a much more fluid market,” she says.

Still, while multiple part-time jobs offer the chance of higher wages, they come with job insecurity.

A yet-to-be-published study by the Institute of Social Studies Trust (ISST), a non-governmental organization (NGO), of 1,438 domestic workers living in the poorest areas of Delhi, has found that lack of job security is only the first challenge. Low-caste workers can be prohibited from using their employer’s toilets or drinking their water, notes Shrayana Bhattacharya, the author of the study. This results in a high level of urinary infections among women.

Workers sit outside a house in the Karkardooma slum

In Delhi, ISST found that the majority of women interviewed reported bladder problems and nearly 40% said they feared to take sick leave. Because most also lack identification cards, they sometimes face police harassment, have trouble enrolling their children in school and are often unable to access government schemes.

Part of the problem is that most domestic workers—unless they’ve had formal instruction from NGOs or others—don’t have any real understanding of their rights, according to Surabhi Mehrotra of Jagori, an NGO that works with domestic workers.

“Most don’t think of this as a form of work. They see it as an extension of something they do at home,” she says. “Before they can negotiate for their rights, they need to see themselves as workers.”

There is also the risk of jeopardizing the job. Kumari, who has two boys and two girls, says the Rs. 2,500 she earns each month is the most secure source of income for the family. Although her husband, a cement pourer, earns more when he works, his income is project-based and uncertain. This is common to many poor families.

Of the husbands of domestic workers, surveyed by ISST in 117 slums in and around Delhi, one-third were casual labourers and the rest, either unemployed or in low-paying jobs as rickshaw pullers, cleaners and waste pickers. At the subsistence level, these women are a critical source of family income.

There’s some evidence to show that as women earn more, their husbands feel emasculated—particularly if they are unemployed. There are also instances of some of the women, encouraged and emboldened by their own abilities, aspiring for more.

An exception

Radha Devi Verma sits shyly at the table at the house of one of her clients, beaming with quiet pride as she recounts her accomplishments.

Since migrating to Delhi 15 years ago from Uttar Pradesh to get a job, first as a part-time domestic worker and eventually a masseur, she’s been able to fund an expensive surgery that may have saved her husband’s life, paid for her mother-in-law’s eye surgery, built a home in her village, and, though illiterate herself, put her four children, two boys and two girls, through school, married her eldest daughter off to a teacher, even presented her son-in-law with a motorcycle. Later this year, she plans to fund a religious festival in her home village.

Her husband has taken on household duties, including cooking, cleaning and childcare, she says, and is delighted that she is able to contribute so much to the family.

Verma’s accomplishments represent an optimistic trajectory for women working as part-time maids and cleaners. The move to the city allowed her to break free of caste-restrictions and acquire new skills that would have been prohibited in the village. Eventually, while working as a cleaner at a beauty parlour, she learnt how to give head and body massages—a profession looked down upon in her village—and built up her own clientele. Her salary went from about Rs. 1,000 per month (as a domestic worker) to nearly Rs.15,000 per month.

Still, Verma is mindful of the caste hierarchy, and is meticulously careful that word of her profession does not get back to her people.

In an ideal world, according to Reiko Tsushima, specialist on gender equality at the International Labour Organization, part-time domestic workers would all end up like Verma, starting with relatively unskilled labour, like mopping and sweeping, and eventually leading to more skilled professions—cooking, caring for children or the elderly, or like Verma, becoming beauticians. However, this is more the exception than the rule.

According to Sanjay Kumar, regional director of Self Employed Women’s Association (SEWA), Verma’s experience is quite exceptional. “There might be one woman in 100 like that,” he says. “Maybe two in 500. Without a catalyst, it’s unlikely.”

In an attempt to provide such a trigger, SEWA has been working in the slums of Delhi, Kerala and Gujarat, informing domestic workers of their rights, helping them to form unions; it will also, eventually, provide vocational courses.

Ranjana Kumari, president of Centre for Social Research, suggests that such unions help increase the opportunities available to part-time workers.

SEWA has successfully unionized at least 400 domestic workers in Kerala. Almost immediately, Kumar says, the women in the union were able to raise their wages by around 40%. They also learnt how to negotiate with their employers.

Today, most women have at least four days’ holiday per month. If they work for more than 3 hours, they are able to have tea or water breaks. Women who are sick can ask another member of the group to go work for them, so they will not lose their jobs. “When they organize themselves, they have a platform to talk about their rights,” Kumar says. “Organizing is key to all of the rights they hope to access.”

While the challenges of their work space are daunting, it is evident that their new-found social and economic empowerment is triggering aspirations among some or at least ensure it for the next generation. Shobha Kumari’s dream is that her daughters will be “educated”, meaning literate (Kumari is not), and capable of making a living independently as skilled workers.

The ISST survey found that although three out of four women surveyed in Delhi said they were happy doing domestic work, almost an equal proportion said they wouldn’t want the same future for their daughters. “I do not want them to do what I do,” agrees Kumari. “It is not good work.”

From homemakers to decision makers

Collectives in Bihar are slowly transforming the social role of women to leading their families as men migrate for work

Madhubani, Bihar: Arhuliya Devi remembers a time when she could barely sleep because of stress. A petite woman with a weather-worn face, she tightens her red scarf around her hair and shudders at the memory.

One of her children was sick with high fever, bad chills and nausea. Her husband was away in Punjab working as a migrant agricultural labourer. She had no money to pay for a doctor, no way to take her child to a hospital even if she could afford it, no way to contact her husband to ask for money, and had four other children to care for.

Because of her poverty and Dalit status, local moneylenders were reluctant to give her a loan. She finally managed to get a small loan—at more than 60% interest—that would take her many months to pay off. It was the turning point for Arhuliya Devi and her family; she realized she could no longer depend on her husband to be the decision maker. She would have to learn to manage on her own.

Much has changed since. After forming a women’s collective of migrant workers’ wives, not only is she out of debt, but also, often, funds her husband’s trips to Punjab. She’s one of a growing number of Madhubani wives who see collectivization as a survival strategy. Such collectives, which often serve as de facto support groups, sources of credit, insurers and decision-making bodies, are slowly transforming the social role of women in rural areas. This is particularly true of Dalit communities that, for at least six months of the year when the men migrate in search of work, are run nearly exclusively by women.

The phenomenon is evident all over India. As men move away from their homes and villages in greater numbers, “an unprecedented change is under way in how the households and communities function”, according to a recent study on women in Rajasthan by the Aajeevika Bureau, a non-profit organization providing services to seasonal migrants.

“In particular, changes are visible in relation to women’s status, responsibility and challenges as they cope with the new reality of long and frequent absence of men—husbands and fathers—from their midst,” it says.

In the village of Jhanjharpur, Bihar, women toil on small wheat patties (pieces of land), often bringing their children along with them to work. Poverty—in the form of pothole-riddled dirt roads, lack of electric lights or vehicles, and small huts with thatched roofs and manure-packed floors—is a fact of life.

New challenges

Less apparent is the dearth of men. For between four and eight months every year, nearly 70% of Jhanjharpur’s male population migrates to places such as Delhi, Punjab, Mumbai and Haryana in search of work, according to Ramesh Kumar, president of the non-profit Ghoghardiha Prakhand Swarajya Vikas Sangh (GPSVS), which has set up self-help groups in the area.

Most men are illiterate, married and landless, and send back remittances to support their families.

Due to the recent droughts, many men are leaving earlier, and staying until later, every year.

According to a study published by the Indian Institute of Public Administration (IIPA) in July, Bihar is the biggest source of migration in the country —nearly 5.2 million people—closely followed by Uttar Pradesh, the vast majority of whom are married men migrating solo in search of work.

Around 84% of the Bihar migrants surveyed said they believed male migration to be on the rise. But the tremendous pressure this puts on women is just beginning to be studied.

Arhuliya Devi describes having to cobble together income from odd jobs such as sharecropping and selling vegetables in the market, as remittances from her husband are irregular.

“Suddenly she will have to manage agricultural expenses, interface with banks, insurance products, sell produce in the market—all things that men usually do,” says Prema Gera, who heads the poverty unit at the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). “It’s very tough.”

A larger issue is credit: Most women can’t easily get a loan without a man. According to the IIPA study, 58% of migrant families from Bihar are in debt to moneylenders. Unaccustomed to dealing with women, some banks and moneylenders simply refuse to work with them, says Gera. “Women are invisible to some service providers,” she adds.

An additional problem is that women do not have title to the property the family owns. “Many have to till their own land if they want to increase productivity, they need to have fertilizer—to get that, they need credit, money—which they can’t get,” says Reiko Tsushima, gender specialist at the International Labour Organization. “They are completely dependent on men to access this system. This is where self-help group can be helpful.”

Changing roles

At a recent gathering in Madhubani, Arhuliya Devi—along with nearly 20 other Dalit women—sat on a dusty tarp in a clearing between tiny open rooms. The group, one of many that have been set up in Madubhani by GPSVS, meets twice monthly to administer small loans and discuss problems.

It might not look particularly well organized, but the women say it’s had a transformational effect on their lives. Prior to its formation, all members of the group reported having been in debt to loan sharks—with interest that ranged from 60-120%. Many also reported chronic health problems, malnourished children and depression—feeling of loneliness and stress.

Such self-help groups have flourished in Madhubani. Introduced nearly 11 years ago by GPSVS, there are now 296 such groups in the region, 80% of which are headed by women, in the absence of men who had migrated in search of work, Kumar says. Although this group is relatively new—just three years old—all its members have already managed to get out of debt. Between them, they’ve saved nearly Rs. 8,400 that members can dip into to pay for health or food expenses. Such common funds can be accessed even to pay for a daughter’s wedding.

The husband of one of the members says that he feels secure now that there is a group to take care of his family when he is away. “In Punjab I only earn Rs. 100 per day, I can’t save that much—now (my wife) is sometimes earning more than me, and taking care of the family. So it’s a great comfort to me,” he says.

One member joined the local panchayat, or village council. She has since secured three solar lights for the village, and is pushing through old age pension applications for 12 of the group members. “Before, I had no information about it, I had no confidence,” she says. “Now I can help the collective to access government schemes.”

When a banker repeatedly refused to open an account for another women’s collective in the village of Gurgipati, they used their collective power to force him. Nearly 100 of them camped out in front of the public sector bank early in the morning, and refused to allow it to open until they were heard. After 5 hours, the banker opened an account for them. No woman has had a problem there since.

Family benefits

UNDP has found that levels of distress migration drop in areas where there are well-established, financially savvy women’s groups. “There is more opportunity created back home because women have access to collective loans, so there’s benefit for the entire family,” says Gera. “This creates more opportunities for men.”

But the new-found power of women in such communities is limited, according to Bina Agarwal, an economist at the Institute of Economic Growth in Delhi who studies gender and land rights. “The men are never entirely away,” she says. “They still have a say in whether or not the women form a collective. In general, NGOs (non-governmental organizations) have to be the catalyst.”

Still, having effected some change through self-help groups, the women are inspired. In the village of Suggapapi, one of the more established groups struck out collectively to address the problem of liquor consumption in the village. They exerted pressure through local police officers and panchayatleaders, staged a public rally and eventually succeeded in shutting down the local liquor store.

Alongside, they mounted social pressure on their husbands by refusing to serve them food until they gave up their drinking habits. Eventually the men had to take a public vow not to drink.